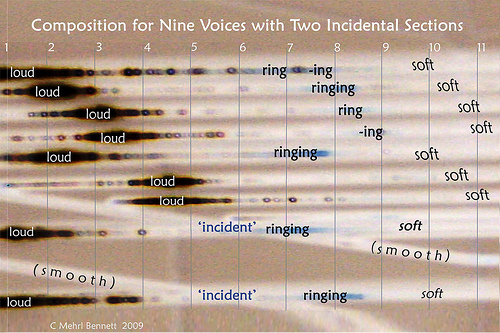

Sound poetry and asemic writing come together for me whenever this question is posed, “How can an asemic poem be performed?” I think it only takes a simple leap of faith to be able to read an asemic poem like a music score and to improvise with the score using asemic sounds. I will begin with two examples to demonstrate how both bubble up from the same well, though these images appear totally different at first glance. The first is the score for a sound poem that I based on a found asemic score, and the second is a black and white typographical visual poem that evolved from a list of smoothie ingredients. In 2009, I took a photo of parallel linear shadows on a wall and messed with the digital file using image software. When I was playing around with the digital file, a combination of Photoshop Elements commands amplified wider and narrower sections in the linear shadows and a saturation of the colors brought out blue areas in the lines. I recognized a sound poem in the results; Wider darker sections equaled louder sound and narrower sections equaled quieter, softer sounds, and blue in the lines call for the ringing of wind chimes or bells. Two vertical shadow lines were scored for quick event performances where they intersected with parallel lines. The image is divided into 10 1/2 measures: each line is performed simultaneously by one voice for each line, two extras to perform the ‘incidents’, and one person to count steadily to 11 to help the performers keep time with the score. Here is the resulting score:

Scanning printed text while moving the paper during the scan produces asemic text when the original text can’t be read for its original intended meaning. Also using computer software, I did some layering and fine tuning until I felt satisfied with this asemic poem:

The element of chance is important in both of these projects. The first project involves natural light and photo technology. A performance of the score involves multiple people making asemic sounds of their own choosing. The second is a form of copy art that involves chance elements of movement and time. There is also a common element of glitch art with the use of computer technology. The results stimulate thinking the same way that reading music scores or text do, but with the use of a broad artistic palette with an inter-media approach: music, literature, poetry, performance art, the plastic arts (including photography and calligraphy), conceptual art, etc.

Asemic writing is a form of visual poetry in that it is a confluence of writing/reading and it often involves the above-mentioned inter-media approaches. There is self-consciously produced asemic writing and there is the serendipity of ‘found’ asemic writing that can be documented in human environments. Human documentation of that which is perceived as asemic writing happens in both urban and in natural environments, such as ant trails on a log, swirling water, the spreading angles of ice on a window, etc. Composition for Nine Voices (the first example in this essay) was ‘found’ in light and shadows on a bathroom wall. The second black and white example involved text that was a recognized language which was then deconstructed in such a way as to make it unreadable as a traditional text.

The artist, writer, or performer might wrinkle a text on paper into a ball and then attempt to read it, or tear it into pieces and reassemble it by chance. Both those techniques have been used to create a kind of “dada” poetry, but a true asemic meaning would result not only in scrambled phrases or sentences but in unrecognizable words. I think the definition of “asemic” must remain fluid, however. Here is a statement about that term written by my spouse, who is also a poet/artist: “Everything is asemic to some degree in that everything is not fully understandable, except perhaps in the multiple, mostly unconscious, regions of the mind. Thus, nothing is truly asemic; everything has meaning,” John M. Bennett, March 2017. John was practicing a form of asemic handwriting in the late 1970’s, which he called “spirit writing”. An example of JMB 1977 spirit writing on graph paper, rubber stamped at the top with “MEAT RECEIVING”, appears in one of Tim Gaze’s first issues of Asemic Magazine (started in 1998). Notice the ambiguity of John’s statement in that “everything is asemic” and “everything has meaning”. There is a kind of “zen attitude” in contradictions, and to be fluid in your thoughts is to be living in the fluxus moment.

German fluxus artist, Brandstifter, in collaboration with the artist, Ann Eaty, asked us to collaborate with them on a project. We recorded our separately improvised vocalization of syllables and sounds found in the scattered letters of alphabet soup pasta. They included the audio in their March 2017 NYC gallery antipodes presentation, paired with two scanned images of the scattered pasta which appears to come out of each of their scanned heads. A year or two previous to Brandstifter’s project, John and I had recorded video of a similarly improvised asemic performance. Improvising, we vocalized asemic and sometimes recognizable words from each other’s scrambling of letters, resulting in the video “Gaez and Vexr”, found at my YouTube site: https://youtu.be/rql_IQvpf5Q

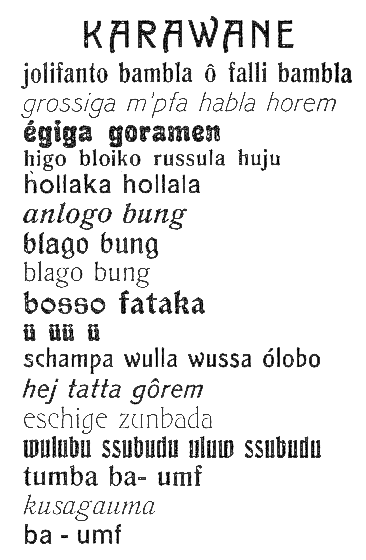

Music can inspire a kind of lyrical singing of nonsense syllables like what is called “scat” in jazz singing. This kind of improvisational thinking is a high art form of asemic language and is one of the inspirations for asemic verbalizing I’ve done in performance venues. That, along with a performance I saw by Lori Anderson decades ago, and YouTube videos or SoundCloud audios of people performing Ursonate, a sound poem by Kurt Schwitters. Jaap Blonk, Christian Bök, and Olchar Lindsann are artists who have successfully undertaken a performance of Ursonate. Schwitters was one of the early Dadaists, though he termed his activities as “MERZ”. Hugo Ball also wrote and performed sound poetry and, along with his partner Emmy Hennings, started Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, Switzerland in 1916 – the very first Dada performance venue. Hugo Ball’s sound poem, KARAWANE, is iconic! The poem image below shows a playful visual presentation where the author uses multiple fonts, some italicized and some bolded, and the straight forward phonetically spelled words are ripe for performance. Ubuweb site has audio files of six of Hugo Ball’s sound poems being performed: http://www.ubu.com/sound/ball.html

“Zaum” was coined by Russian futurist Velimar Khlebnikov (b.1885 d.1922) and poet/theorist Alexei Kruchonykh for a kind of suprarational, transcendental, phonetic, poetic language of the future. Paul Schmidt, an English translator of that Russian genre coined the term “beyondsense” in relation to Zaum because of the emotions and abstract meanings he felt were more forcefully conveyed without the intervention of common sense. Igor Satanovsky (b.1969, Kiev, Ukraine) is a bilingual Russian-American poet/translator/visual artist who moved to the United States in 1989. On a Facebook page created by Satanovsky to commemorate “Zaum Day” [January 7th, 2017], he posted two interesting Zaum poems. “Sec” by Daniel Harms (Daniil Kharms), a Russian poet who was publishing in the 1920’s, and “KIKAKOKU!” by Paul Scheerbart, a German poet who published this early phonetic poem in 1897 in his book called: I love you! A railroad novel with 66 interludes. New Edition: Pub: Affholderbach & straw man, 1988, p. 278. Listen to this excellent recorded performance of KIKAKOKU! on You Tube by the Uruguayan poet, musician, and performance artist, Juan Angel Italiano in collaboration with Luis Bravo, poet/teacher extraordinaire. https://youtu.be/QgMGYXyRVTw

Italiano has also made many videos and audio recordings of poetry and sound poetry performances by Luis Bravo, John and myself, and others.

Many Pentecostal and other charismatic churches strive to inspire their members to “speak in tongues” when they are baptized, a form of asemic language known as “glossolalia” or “Ecstatic language”, which is also embraced by charismatic movements in Protestant and Catholic churches. There is ancient evidence of this phenomenon in early pagan temples and Ancient Byblos (1100BC). Here is a quote from Dr. John R. Rice’s book, The Charismatic Movement, pp. 136-139: “Some Christians talk in tongues. So do some Mormons, some devil-possessed spiritists, (and) heathen witch doctors in Africa and Asia. Ages ago many heathen religions talked in tongues. It is not of itself necessarily of God.” There are preachers who claim to interpret glossolalia as if it were the word of God; however, I think asemic writers see glossolalia as a mimicking of language, a symbolic façade, and a tool to “free up” the areas of the human brain that process language.

The asemic approach to invented language and/or calligraphic gestural abstraction is an unrestricted, open process. Do not forget that as humans we start out linguistically by voicing baby talk, which is a beautiful naive form of asemic language. A young child’s art has an innocence and free spirit that is often lost later on in middle school when a tightness forms around attempts at an artful representation of images. Preconceptions about the object being drawn and about what encompasses good art or poetry can get in the way of actually ‘seeing’ what is there and rendering or expressing it. The same thing can be said about the academic approach to language and literature, and more currently, the effect of ‘workshop poetry’ on writer’s sensibilities. On a more populous level, many people in the USA have come to accept clichés and greeting card verse as good poetry. I try to guard against using clichés, as they are a tempting and easy solution for expressing a feeling.

We, as artists, must be open to the creation end of literature and poetry and search for meaning without the hindrance of preconceptions. Meaning is found in the act of creation, interaction with nature and the media we chose to convey our thoughts, and in intuitive thought processing. Often the art is in the doing as much as in the artifact that remains. The asemic approach encourages new ways of reading and thinking and reaches across language barriers. Being open to interpretation and change is ‘in the reading’ as well as ‘in the writing’. Any meaning the reader construes is a correct translation. Asemic meaning or non-meaning is not a static thing, but a meaning in flux.

There are public places in urban settings where event notices or advertisements are posted and then torn down with bits that remain in layers upon layers, often resulting in a colorful patina of collaged text. This is “found” asemic writing, but the collage technique is also a very deliberate human initiated process in asemic writing and art. The collage technique began with artists like Hannah Höch and others in the Dada movement that took hold around the end of WWI in Europe. The absurdity of the chaotic realities of damaged human lives that came about as a result of the war was greater than any absurdity an artist or writer could imagine. The new media of photography brought reality and current events into the tool box of artists. The act of creating a composition with typography and photographic images was a way of trying to create order out of chaos. Urban graffiti is a similar response to absurdities of real life. Amid those urban ‘found collages’ of posted leaflets, we also find spray painted graffiti. Graffiti ‘tags’ and stylized calligraphy may appear as asemic to the average onlooker, though it usually has a specific meaning to the artist/author and maybe their immediate circle of peers.

The creation of glyphs, symbols, new words, and poetic sounds might start out in a vacuum and then start to gain meaning within a cultural milieu. Or it might only be known to one living person who dies with that knowledge, perhaps leaving behind an artifact of that language. That artifact will be perceived as asemic by the rest of humanity, though anthropologists may attempt to decipher the meaning, for example, that of ancient Mayan glyphs. It is a very human and natural instinct in all of us to be attracted to glyphs, symbols, new words, interesting typography, and sounds because of a basic need to read or interpret signs in the world around us and to use these as tools to communicate with others.

Citing the NY Ctr for Book Arts website http://centerforbookarts.org/making-sense-of-asemic-writing/, Wikipedia states that “The history of today’s asemic movement stems from two Chinese calligraphers: “Crazy” Zhang Xu, a Tang Dynasty (circa 800 CE) calligrapher who was famous for creating wild illegible calligraphy, and the younger “drunk” monk Huaisu who also excelled at illegible cursive calligraphy”.

A Japanese calligrapher, Shiryu Morita (b.1912) sought “a common universal language that was centered on spontaneous gestural abstraction.” In his work, he wanted to “reconceptualize calligraphy as a contemporary artistic medium while seeking to rise above the barriers between cultures so as to generate a new international art.” Source: http://www3.carleton.ca/resoundingspirit/morita.html

In America in the 1950’s with the rise of modern abstract expressionism and its male icons, we had something akin to asemic writing in the paintings of Jackson Pollock (though he never acknowledged any connection with writing in his work), Cy Twombly Jr., and Brion Gysin (who, aside from his asemic paintings, literally inspired and influenced William Burroughs with his experimentation with the cut-up technique). Today, asemic calligraphic writing appears in art museums globally, including beautiful examples from Islamic artists.

In this digital, post-modern age [computers and fast paced work environments and expanding online social networking], asemic writing is more accepted, recognized, and appreciated on a global scale. It can be created via interdisciplinary genres of writing and other art forms such as the visual arts; including digital art and contemporary forms of drawing, typography, and photography, video, sound, and performance arts. “Intermedia” is a term used for these interdisciplinary arts practices that have developed between separate genres, and was an important concept promoted by Fluxus artist, Dick Higgins. In the past few decades, many art departments in universities have begun to offer degrees in intermedia.

In November 2008, visual poetry finally received some attention from Poetry Magazine, which was founded by Harriet Monroe in Chicago, 1912, and today is one of the leading monthly poetry journals in the English-speaking world. This attention came in the form of an article by Geof Huth which offers comments on a portfolio of twelve works by thirteen visual poets. With his selections, free wheeling asemic poetry is given as much credence as more tradition concrete visual poetry. It is to Huth’s credit that he puts forth both visual poetry as a whole, but also the asemic markings in the portfolio, as poetry. Huth’s article is online at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/articles/detail/69141

Asemic poetry is harder for the academics to accept than visual poetry with recognizable words, and there is a faction of visual poets who see it as part of the plastic arts rather than a form of visual poetry. Yet, no matter how asemic writing is categorized, there can be no denying that it has garnered attention in the past couple decades. Many examples are published in a 2010 anthology edited by Nico Vassilakis and Crag Hill titled “The Last Vispo”. More about that important anthology, for which I am one of four contributing editors, is online here: http://www.thelastvispo.com/

One of the first people to curate an exhibit of asemic poetry was Tim Gaze, an Australian poet who has written about asemic poetry and was one of the first of our contemporary circle to be interviewed about asemic writing. Jim Leftwich (Roanoke VA) was working around the same time as Gaze in asemics. Michael Jacobson (Minneapolis MN) discovered Tim Gaze’s asemic magazine in 2005, and drew parallels with the novella he was working on, “The Giant’s Fence.” http://www.commonlinejournal.com/2008/12/interview-tim-gaze.html is a link to an interview with Tim Gaze who hosts a website at http://www.asemic.net; also see http://www.asymptotejournal.com/visual/michael-jacobson-on-asemic-writing/ for an interview with Michael Jacobson, who administers a blog and a Facebook page by the same name called “The New Post-Literate”. Luna Bisonte Prods publishes works by experimental writers and poets, and recently published three volumes by Jim Leftwich titled “rascible & kempt: meditations and explorations in and around the poem”. Find descriptions and previews of all three “rascible & kempt” volumes at http://www.lulu.com/spotlight/lunabisonteprods These volumes have examples of Jim’s asemic poetry as well as interesting discussions about the current milieu of experimental writers and their work. A few examples of the current terminology he uses for what he sees as today’s experimental writing are quasi-calligraphic drawing, writing-against-itself, and polysemic writing.

The final image I present here is an example of a straight forward back & forth asemic writing I did through snail mail during mail art exchanges with Forrest Richey, aka Ficus strangulensis. The calligraphic practice sheet was set up by me and mailed to Ficus and other mail art contacts. The first line on this card was his and we alternated until the card was full.

The entries made from a continuous line are a form of automatic writing, or ‘spirit’ writing. The surrealists, inspired by Freud and the unconscious mind, were doing something similar called surrealist automatism. When I was an MCAD art school student in the early 1970’s, I filled an entire sketchbook with the sort of doodling you see on the last line. I’ve also seen that kind of continuous line patterning piped onto the surface of our wedding cake by an Amish baker and cake decorator, so I know it’s nothing new. But I enjoyed a meditative state of mind as I was doing it. I never titled the drawings, instead, I simply documented my start and stop times. Another artist, Billy Bob Beamer from Roanoke VA, has a similar kind of ‘in the zone’ automatism approach with what he calls his ‘word dust’ pencil drawings. See this web link for more on BBB: http://www.outsiderart.info/beamer.htm

C. Mehrl Bennett, Columbus OH, USA

Artist, poet, mail artist, writer, audio experimenter, associate editor of Luna Bisonte Prods

March 2017

This post is packed with so much cool info! Thanks!

LikeLiked by 2 people

i was not able to read all at one time, so much informations, i have to come back again. thx!

LikeLiked by 1 person